Bliesbruck-Reinheim: Celtic Princess, Roman villa and Gallo-Roman site.

Posted on Aug 24, 2013 in category

Bliesbruck-Reinheim is a unique archaeological site in many ways:

- It is located within the borders of two countries, Germany (the State of Saarland) and France (the Departement of la Moselle) - a collaboration that began in 1988 resulting in the creation of a European Archaeological Park.

- In Reinheim, three Celtic barrow-style graves of the early 'La Tene' Iron Age period (circa 400 B.C.) have been excavated since the 1950's, one of which is the famous 'Celtic Princess' tomb. A restoration of this tomb in a museum 100 metres from the original burial site, which was a quarry and is now a fish pond, enables visitors to appreciate the layout of the tomb including reproductions of original artefacts. Nearby Saarbrucken Archaeological Museum, definitely worth a visit, has the privilege of displaying the genuine articles!

Reconstructions of burial mounds, one of which was nicknamed 'Katzenbuckel' or 'cat's arched back', greets visitors as they enter the 'Celtic Princess' museum. The museum is located to the right of a modern sculpture of the figurine that was found on the lid of the bronze flagon.

.aspx?width=450&height=299)

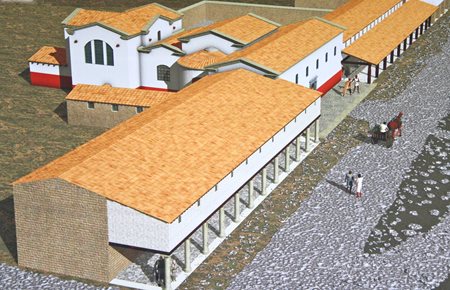

- Also, in Reinheim is the 6 hectares site of a grand Gallo-Roman villa (dated beginning of the 1st century A.D.) with foundations showing evidence of hypohaust heating in several rooms of the main residence (80 m x 62 m), a private bathhouse and a luxurious pool. A large court measuring 300 m x 150 m adds to its impressive dimensions along with 12 large outbuildings that are placed at regular intervals within this huge courtyard. Some of these large barn-like structures, which were probably used for storage of cereals, have been reproduced and now house a museum, restaurant and teaching facilities.

Looking south over the villa's one hectare main residential building with the living section, bathroom and cellar located in the west wing (right). It is presumed that the villa, whose grounds were 4-5 hectares, was owned by an elite Gallo-Roman family. It had its origins in the beginning of the 1st century A.D. and enjoyed its heyday in the first half of the 3rd century A.D.

- Within 250 metres of the Gallo-Roman villa is a relatively small settlement or 'vicus' of approximately 20 hectares dating from 30-40 A.D. Goodman (2007) prefers the term 'non-urban secondary agglomeration' to describe it because it was sited at least 100 kms from towns such as Metz (capital of the Mediomatrici tribe and renamed Dividorum under Roman rule) and Trier (capital of the Treviri tribe and renamed Augusta Treverorum). In addition, the term 'non-urban secondary agglomeration' has no-known Roman legal status implications (P.J. Goodman, The Roman City and its Periphery from Rome to Gaul (Oxford, 2007).

Many ovens were found in these limestone-foundation, terraced houses (houses 4 and 5 north part of west craft district) that date from the middle of the 1st century A.D. to their demise in the middle of the 3rd century A.D. The ovens proved that this non-urban secondary agglomeration produced commercial bread and iron/bronze making, probably to mainly service the many needs of the nearby villa.

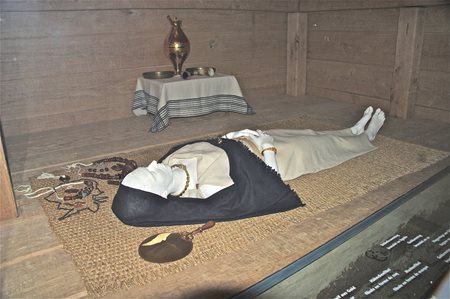

A very special feature of my visit to Bliesbruck-Reinheim was a personal tour of the site by Bliesbruck's enthusiastic and affable archaeologist, Michael Ecker. We began our tour at the reconstructed barrow tomb of the 'Princess of Reinheim' that measured 23 metres in diameter and restored to some 4.7 metres in height. Within the separate tomb museum is the reconstructed wooden funeral chamber itself measured 3.5m X 2.70m X 0.90 m . A respectful ambiance is maintained within the tomb museum helping to create a whisper zone. This ethical approach to displaying a burial recreation has also proven to be very successful in focusing previously noisy students.

The 'Princess' was positioned north to south (no skeleton survived except for traces of two teeth) and she wore a gold, twisted torc around her neck, a gold bangle on her right wrist, 2 gold rings on her fingers and 3 rings made of gold, glass and lignite on her left forearm.Left of her head a large quantity of amber and glass beads were found suggesting a wooden jewellery box was positioned there at the time of her burial.

A bronze mirror with coral decorations on the handle and a female 'caryatid' figure with upraised arms, has also led most historians to believe that the deceased was female (see A.M. Moyer's, "Deep Reflection: An Archaeological Analysis of Mirrors in Iron Age Eurasia", University of Minnesota Dissertation 2012).

At the rear of the tomb is positioned an impressive drinking set that included two bronze bowls, two drinking horns and a magnificient locally-made bronze flagon with a strange human-headed horse on its lid as well as incised Celtic designs on the flagon's exterior .

This drinking flagon is very similar to the one found in another Celtic La Tene 'female' tomb in Waldalgesheim near Mainz, Germany.

A close-up of the gold torc with cast human heads. It measures 17.2 cms in diameter and weighes 187.2 gms

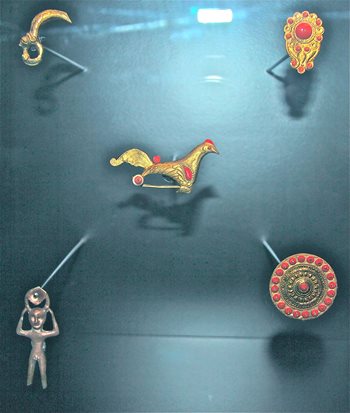

Reproductions of the bronze and gold fibulae some with coral inlays and rooster designs.

Here is the genuine exhibit of 'Goldener Ringschmuck, Furstinnengrab von Reinheim' 4, Jh. v. Chr. - photo courtesy of Stiftung Saarlandischer Kulturbesitz.

From a nearby hill, Michael Ecker impressed upon us the huge proportions of the Gallo-Roman villa. Although villas played a very significant role in Roman Gaul representing more than 1/3 of farms, it still needs to be kept in context; small farms or individual plots of land worked by tribal 'peasants', who lived in nearby villages, were the mainstay of the Gallo-Roman countryside (P.Trostard-Vaillant, "Revisiting Ancient Gaul", CNRS International Magazine, no 19, Oct. 2010 p.17). Roman Gaul was still "a world of villages" whose largely pre-conquest elite soon resided between their new urban residences and their rural estates (G. Woolf, Becoming Roman - The Origins of Provincial Civilization in Gaul, Cambridge, 2003, p.141).

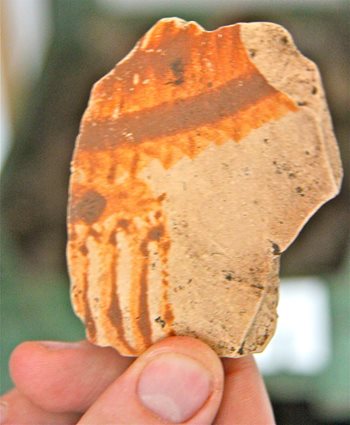

The villa of Bliesbruck-Reinheim was not a fashionable 'suburban' villa like many that surrounded Rome, it was a functional, working rural estate albeit luxuriously decked out with stone and bronze statuary, wall paintings, stone columns and a private bathhouse. There was no 'halo' of villas nearby, it truly dominated rural life around the Blies Valley and beyond. Michael generously showed us his most recent excavation site in the grand courtyard which has turned up some interesting pottery sherds. In fact, Michael was elated to find another overlooked sherd from an incomplete ceramic vessel back in the laboratory.

Excavation site on the west side of the courtyard where the pottery was found.

Michael Ecker was very pleased to discover another pottery sherd to add to his growing collection.

Back in the laboratory, the magnificent pottery sherd is revealed!

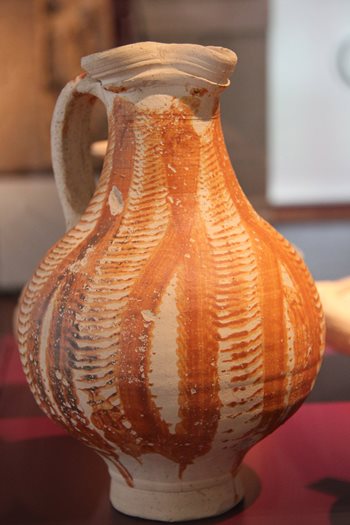

This 3rd century A.D. jug of unknown provenance is on display in the Trier Archaeological Museum. It seems to have a similar pattern to our Bliesbruck-Reinheim find. It would be nice ('wishful thinking') if it was made by artisans who worked and lived in the villa's satellite settlement!

Although the nearby non-urbanised secondary agglomeration boasted a large bathhouse complex from the late 1st century A.D. (possibly gifted to it - euergetism-by the wealthy villa owners who may have become like ruling oligarches), the villa itself had a private bathhouse.

.

Remains of the private bathhouse's hypocaust heating can be seen here in the foreground along with traces of circular steps (right-background) that led into a pool. It is estimated that a mere 5% of the Roman Empire's population lived in privileged circumstances usually living in towns, cities and/or on country estates such as Bliesbruck-Reinheim (see Arjan Zuidenhoek's, The Politics of Munificence in the Roman Empire, Cambridge, 2009 p.5).

Thirteen years ago in 2000, an equestrian iron mask with bronze plating was found at the rear of one of the courtyard's large outbuildings. Used in ceremonial or sporting events, this hinged-visor was attached to a cavalryman's helmet. Although over one hundred of these visors/helmets have been found throughout Europe, it is still a fascinating find. The above photo is courtesy of Stiftung Saarlandischer Kulturbesitz and is officially called, 'Paradesmaske eines Romischen Reiters, Reinheim, 2.Jh.n.Chr.' (many thanks to the Saarbrucken Museum for Prehistory and Early History for permission to publish two of the above photographs).

Only 250 metres from the Gallo-Roman villa in Reinheim, Germany lies the Gallo-Roman settlement in Bliesbruck, France. Excavations reveal the settlement is made up of 14 terraced buildings stretching 800-900 metres along both sides of a secondary 'B' road which is parallel and nearby to the old Roman road. Two business/craft districts lie either side of the 'B' road: houses 1-7 to the north and houses 8-14 to the south.

The north part (build. 1 to 7) reveals constructions with limestone rubble and pointed lime mortar. Generally, the design of most buildings here consists of a portico facing the street which is supported by masonary pillars. A rectanguar room or two, sometimes with a cellar, lie beyond the portico followed by a large square central room with several smaller rooms at the back of the house (probably extensions over time in 2nd century A.D.) usually with hypocaust floor heating or lime concrete flooring.

House No.6 reveals a typical craft district design.

The south part of the settlement (build.8-14) reveals simple shop designs consisting of a large rectangular room (workshop/shop) with a mud floor, now gravel, opening onto a stone-mounted, timber-pillared portico.

Building no.8 (south part of craft district) had three columns set on sandstone bases and a cellar to the rear. A shop or workshop was situated in the large rectangular room that fronted the road (red gravel). Tiles were used for roofing.

The only public building found to date is the thermae or bathhouse complex. Initially built at the end of the 1st century A.D. but extended over two centuries, it is located on a side street, south-west and parallel to the main artisanal road. The bath complex is monumental consisting of a large central section with numerous baths, a courtyard with a central pool, shops flanking the entrance and, in addition, on its north side, the complex extended into a building containing workshops and shops. Not a bad status symbol for a non-urban secondary agglomeration miles from a large town!

An artist's interpretation of the Bliesbruck-Reinheim thermae with its imposing high stone walls and terracotta tiled roof.

In the foreground-right, a large furnace made of big stone blocks and brick flooring, heated the caldarium (hot room) with its pool and metal boiler.

By standing on an elevated platform over the excavations, visitors gain a good view of a reconstructed hypocaust system.

Workshops and shops were attached to the thermae on its northern side and a substantial shelter now protects the bathhouse complex. Fire was evident in excavations which occurred around the middle of the 3rd. century A.D. when the region was ravaged by invading Germanic tribes. The site was repopulated in the 4th century but with far fewer people.

A final thing that has stumped archaeologists at Bliesbruck-Reinheim is the large number of pits and shafts at the archaeological site. Some 100 pits and 50 shafts (the latter with neat dry stone walling) have been discovered. Complete vases have been found in some along with fragments of tiles, stones and animals' bones; otherwise, nothing substantial has been unearthed. However, nineteen of the holes at the back of the West Quarter were found to be latrines after chemical analysis.

One of the intriguing shafts at Bliesbruck-Reinheim Archaeological Park. What was their function?