Berlin's Pergamon Museum: The Altar of Zeus

Posted on Jan 31, 2014 in category

Last year over one million people visited Berlin's Pergamon Museum which is located on 'Museuminsel' or Museum Island, an UNESCO World Heritage Site (1999), along with four other museums. The five museums were constructed on a former Prussian palace's pleasure garden or Lustgarten in the middle of the Spree River with the first museum opening in 1830 to calls of 'Athens-on-the-Spree'. The Pergamon Museum was first opened in 1902 to a fanfare of jingoistic praises towards the relatively new Wilhelminian German Empire. However, it was closed within six years due to inadequate design features and a new Pergamon Museum complex was conceived by both architect, Alfred Messel (1853-1909) and art historian, Wilhelm von Bode (1845-1929) ; however, it was not completed until 1930 under the Weimar Republic .

Damage from World War II is still evident on the museums' stone facades and colonnades. The Alte Nationalgalerie is on the far right, the Pergamon Museum is centrally located in the photo and the Neues Museum is on the far left of the photo. A masterplan intends to link four of the five museums to create a unified experience along an 'archaeological promenade'.

The Altar of Pergamon was dedicated to Zeus. It was built from Naxian and Marmara regional ashlar marble and functioned as a sacrificial altar within an ensemble of urban structures such as temples, a royal palace, library, theatre, gymnasium, baths, public market, arsenal and barracks, all located on a steep acropolis. An alternative view of the structure's function is that it was a heroon or cult shrine to Telephos, the city's mythical founder. (A.S. Faita, "The Great Altar of Pergamon: The Monument in its Historic and Cultural Context," vol.1, Ph.D., University of Bristol, 31 Aug. 2000, p. 26).

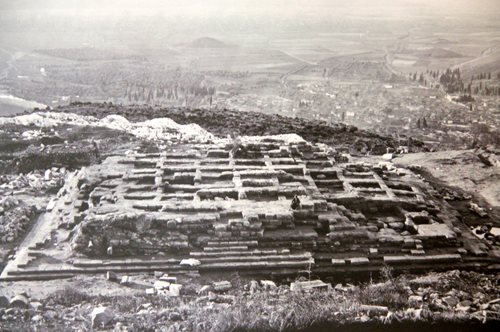

A view of the ancient Pergamene acropolis (approx. 330 metres in height) from the outskirts of Bergama. Strabo, Geography, XIII, 4.1 labelled the citadel a "treasure-hold" of 9.000 talents on a "cone-like" mountain that ends in "a sharp peak."

Another view of the acropolis from the Via Tecta or sacred way (AD 2nd century) which led to the famous healing centre called the Asklepieion. Originally founded near a spring in the 4th century BC some three kilometres from the acropolis, the Asklepieion expanded towards the acropolis and by the 2nd century AD the precinct was only 500 metres from it. The famous school of Galen, the physician, helped Pergamon continue its prestigious reputation as a hub of learning throughout Roman times.

Most likely built by Eumenes II (197-159 BC) or possibly Attalos II (159-139 BC) as a thank-offering for military victories against the Galatii (Gauls), the Altar of Pergamon is truly a 'miracula mundi' (wonder of the world). Very few direct ancient writers' references to Pergamon's Altar exist apart from Lucius Ampelius' 'Liber Memorialis' ( c. 2nd cent. AD):

" At Pergamon there is a great marble altar 40 feet high [approx. 12 metres] and with extremely large sculptures, it consists of the battle of the Giants." (8.14)

and also, John's 'Book of Revelation' where it is largely agreed among academia that, 'Satan's Throne', is a reference to the altar's design and serpent figures.

Pliny the Elder in Nat. Hist. V:33 refers flatteringly to Pergamon as, "by far the most famous city in Asia," as does Strabo in Geography XIII.4.1 with "famous city and for a long time prospered along with the Attalic king," both of whom help to reinforce the long-held view that Pergamon was the "chief seat of culture and learning," in Asia Minor (Charles Perkins,"The Peregamon Marbles. I. Pergamon: Its History and Its Buildings," The American Art Review, vol.2, no.4, Feb. 1881, p.146).

An obscure reference to the Altar of Pergamon was written by Pausanias in Description of Greece 5.13.8 when he compared the two Altars of Zeus at Olympia and Pergamon:

"It [Olympia] has been made from the ash of the thighs of victims sacrificed to Zeus as is also the altar at Pergamon."

Stella Faita (Ibid.,2000, p.72) raises the possibility that the Altar of Pergamon was built over an earlier cult structure which was dedicated to the Kabeiroi, the two children of Zeus and Kalliope (although many sources say the children belonged to Hephaistos and Kabeiro!).

Site of the sparce remains of the Altar of Zeus at Pergamon as seen from the Sanctuary of Athena (the oldest structure on the acropolis dated 4th century BC) which begs the question how did the magnificient structure end up in one of Berlin's museums?

In AD 1871 Carl Humann, a German engineer, whilst working for the Ottoman sultanate surveying roads and railway construction, discovered the first dramatic sculptures from the Altar of Zeus. Initially Humann's small assignment of two sculptures to the Berlin Museum was overshadowed by the German archaeological successes then proceeding at Olympia. However, Humann took Germany by surprise in 1879 with his next much larger delivery of 462 crates of artefacts from the Altar of Pergamon. For a mere 20,000 francs Humann and the Berlin Museum secured a deal from the Ottomans that "swept Germans off their feet" (J. Overbeck 1894).

Carl Humann (second from left) with fellow excavators in 1897

Praises for the Altar's Hellenistic art came thick and fast overturning a commonly held belief among academia at the time that the Hellenistic period was a period in cultural and artistic decline. The Altar's complete installation or 'restitution' (not a historical original - a created imaginary ensemble!) in 1902 put the Berlin Museum on an equal pedestal with the prestigious British Museum thus greatly boosting the dignitas of a relatively new German Empire ruled by the Hohenzollern family (L. Gossman, "Imperial Icon: The Pergamon Altar in Welhelminian Germany," The Journal of Modern History, vol. 78, no.3 Sept. 2006, p.579).

A view of the foundation site of the Altar of Pergamon during its excavation over three campaigns from 1878-1886. Most of its famous 'reconstructed' Altar sculptures were not retrieved in situ but found within retaining and defensive walls built widely throughout the acropolis and over an extended period of time.

A model of the ensemble of Hellenistic structures on the acropolis of Pergamon. As the Attalid kingdom adopted a more independent foreign policy especially after Attalos I 'Soter' stopped paying a heavy tribute to the Gauls, Pergamon's beautification and patronage of the arts became the beneficiaries of the Attalid regime's growing self-confidence (A.S.Faita, 2000, p.33).

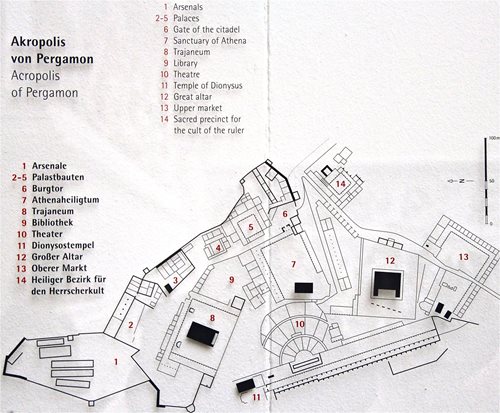

A plan of the acropolis which places Pergamon's 'Altar of Zeus' (12) in its architectural context

Marxiano Melotti in "Archaeological tourism and economic crisis: Italy and Greece," Electryone, vol.1. Issue1, 2013, pp.29-53, relates how this Hellenistic reconstruction influenced many conservative German architects including Albert Speer, Hitler's chief architect. Moreover, Melotti believes that Pergamon Museum's 'Altar of Zeus' was a precursor to today's possibly heritage-wrecking trend of falling over backwards to cater for the demands of tourism at historical sites and monuments by interweaving culture and amusement, so called 'edutainment'. Melotti believes that the Altar of Pergamon is "self-referential", more an end in itself than an accurate means to represent history.

S.M. Can Bilsel (2003) also calls the Pergamon Altar an "imaginary ensemble" and that it, "sacrificed the specificity of the fragment for the generality of the whole." (S.M. Can Bilsel,"Architecture in the Museum: Displacement, Reconstruction and Reproduction of the Monuments of Antiquity in Berlin's Pergamon Museum," Princeton University Ph.D., Nov.15, 2003, p.15).

Despite these criticisms and reservations, Pergamon Museum's Altar radiates architectural grandeur that was used by the Attalid kings for "self-definition" and of course, "self-glorification" (S.Faita 200, p.1).

Over 1 million tourists a year enjoy the close-up experience of the 24/25 stepped monument with its wrap-around carpet-like, highly emotive sculptural masterpiece.

Its features include:

- dimensions of the monument: 36.8 metres (east/west) x 34.20 metres (north/south)

- monumental platform set on a podium of square stones

- wall of podium decorated with a large, high relief frieze that depicts the Gigantomachy, a battle between the gods and the giants; a metaphor for the 'civilised' Attalid kingdom's victory over the 'uncivilised' Gauls

- dimensions of the Gigantomachy frieze are 2.30 metres (H) and 120 metres (L)

- a great staircase led to an altar in upper structure dedicated to hero, Telephos, founder of the city

- a second, unfinished 'Telephos' frieze decorates the upper sepulchral monument: 1.30 metres (H) x 60.60 metres (L) with inscription "Queen...for benefits bestowed." Possibly in honour of Apollonis, mother of both Eumenes II(197-159 BC) and Attalos II (159-139 BC). Only 43 of an estimated 74 panels survive.

- pottery finds around the altar confirm a date around the 160's BC that is Eumenes II's victory over the Gauls

- 5 inscribed sculptors' names have survived e.g. Orestes and Theorrhetos from Pergamon, an Athenian named Dionysiades and 2 Rhodians as well as scanty evidence of over 11 more sculptors' names (Faita 2000, p.23)

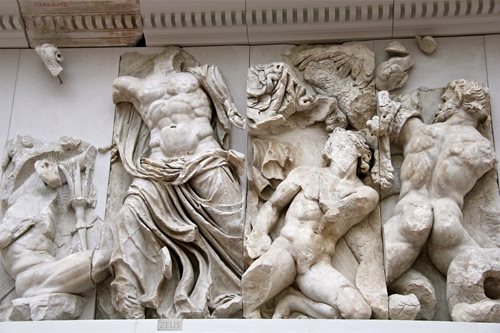

Athena, patron goddess of Pergamon, (second from left) and Winged Nike (fourth figure) battle against the giant earth mother, Gaia (third figure) and her son, Alkyoneus, who is immortal but only if his feet never leave his mother's ground (first figure). This east section of the frieze would have appropriately first greeted worshippers as they descended from Athena's Sanctuary to view the east wall of the Altar; the steps and entrance to the Altar were on the west side which overlooked the city and valley below. Fifty five inscriptions, masons' marks and gods' names on cornices assisted in positioning the figures; however, only three of those inscriptions were found in situ, thus it was a difficult task to identify particular figures and to be certain about the themes of the Gigantomachy.

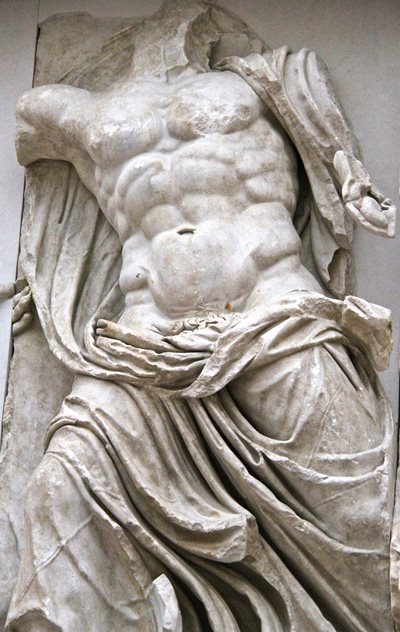

Zeus (above) is about to throw his thunderbolt at a Titan whilst his eagle (below) helps to distract Porphyrion (below far right), one of the leaders of the Giants.

An estimated 120 panels were used on the Altar's Gigantomachy frieze of which 104 are preserved in varied condition. Over 100 over life-sized figures are preserved. According to S.Faita (2000), there are four aspects of the Gigantomachy that help to make it so special:

- a variety of life including animals and birds such as lions, dogs, eagles, horses, fish and sea-horses

- dramatic use of drapery adds continuous movement and eye direction to each panel such as the drapery on Zeus (above)

- intense emotional expression especially on the defeated giants' faces bathes the work in "pure pathos"

- avoidance of a monotonous processional-like effect by creative design of figures

A lion mauls a giant whilst the lion goddess Ceto is about to launch a lance (north frieze)

It is easy to forget that the sculptural friezes were painted in antiquity adding another dramatic realistic dimension to this Hellenistic art. Other decorative artefacts have also been excavated from the acropolis such as mosaics and free-standing sculptures.

An example of 'opus vermiculatum' mosaic of a parakeet 'psittacus torquatus' excavated from Room 3, the Altar Chamber, in Palace V (2,240 m2) Pergamon Acropolis. Certainly a contrast from the hurricane-like struggle of the Gigantomachy frieze. A mosaic in Room 1, Palace V had the mosaicist's name recorded on the work: "Hephaistion made this."