A Visit to some Celtic Heritage Sites in Germany: Kelheim and Manching

Posted on Dec 17, 2013 in category

Celtic 5th century BC sites in southern Bavaria reveal an increase in the production and use of iron for tools, jewellery and weapons. Trade in pottery (mostly hand-made), bone/antler carving and textiles also increased significantly during this late Hallstatt period (750-450 BC).

A child's inhumation in Grave 7 at Kelheim's Hallstatt cemetery.

Locally produced ceramic artefacts from Grave 23 at Kelheim. Grave 11 (in cemetery plan, below far right bowl) was one of the most adorned Hallstatt grave sites at Kelheim.

A bronze armring from Kelheim (3rd century BC)

It was not until the 2nd century BC (La Tene period: 450 BC-20AD ) that larger 'urban' settlements or hillforts called 'oppida' began to dominate the Bavarian landscape in terms of building construction, manufacturing on a mass-produced scale such as glass, coins/iron production and external trade such as fine pottery, bronze wine jugs and/or amphorae (P.S. Wells, "Creating an Imperial Frontier: Archaeology of the Formation of Rome's Danube Borderland," Journal of Archaeological Research, Vol. 13, no.1, March 2005, p.56).

A Celtic wine jug (1st century BC) excavated at Kelheim.

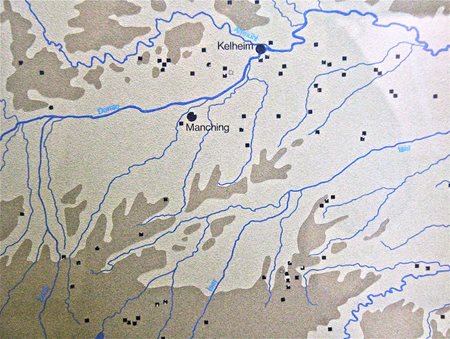

Two of these southern German Celtic oppida sites that stand out are Kelheim and Manching. Each are located near the Danube River and are only 34 kilometres apart. It is possible that both oppida belonged to the Vindelici tribe with the former oppidum specialising in iron production for the latter (P.S. Wells, Ibid. 2005, p. 58).

Kelheim or Oppidum Alkimoennis was flanked by the Altmuhl and Danube Rivers. The nearby Michelsberg high plateau where over 6,000 pits have been unearthed reveal a location which held abundant deposits of limonite, an ore that can be used in iron production. Timber supplies were also abundant in the region; thus, allowing a rich source of charcoal for furnaces/kilns and the construction of a 6.5 kms defensive wall called 'murus gallicus' that enclosed an area of 600 hectares.

The yellow lines show the defensive walls of Kelheim oppidum, the black dots scatterred represent iron slag remnants, black semi-circles are deliberate iron dumps and the bone shaded areas are iron ore prospecting sites.

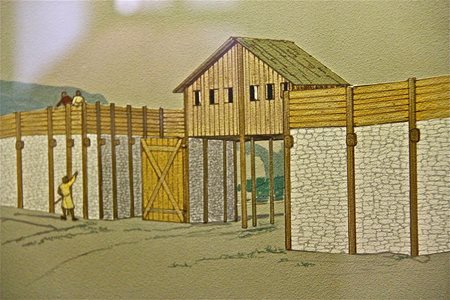

An artist's interpretation of 'murus gallicus' - Kelheim-style called 'pfostenschlizmauer'. Long timber beams are inserted vertically in the ground in front of an earth rampart which is faced in stone. Between the upright timber beams, more timber beams are positioned horizontally at the top in order to strengthen the entire structure.

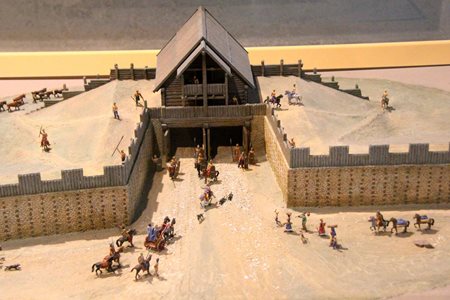

A reconstruction of a fortified gateway at Kelheim.

Slag heaps in the valley below the plateau, where most of Kelheim's 500-1,000 population lived, have been dated from 150 BC to the birth of Christ. Accordingly, Kelheim has been described as "an early Pittsburgh" (P.S.Wells, "Iron Age Kelheim: A MIlltown Blossoms on the Danube," Archaeology, 1988, pp60-61). An excavation of the Kelheim settlement in 1987 by Minnesota University found 1,991 fragments of iron ore by-products as well as finds like nails, knives, chisels and belt fasteners weighing 12,467.5 gms. Pottery finds included 11,722 Late Iron Age sherds weighing 63,497.5 gms. with a wide range of styles similar to those found at Manching oppidum. A large lump of unformed bronze was also found which possibly reveals bronzesmith artisans working side by side with other craft workers rather than in specialised areas within Kelheim's oppidum (P.S.Wells, "Industry, Commerce and Temperate Europe's First Cities: Preliminary Report on 1987 Excavations at Kelheim, Bavaria," Journal of Field Archaeology, Vol.14, no.4 (Winter 1987), pp.399-412).

A bronze arm bracelet (left) and a sapropelite armring (left) - 3/2 centuries BC.

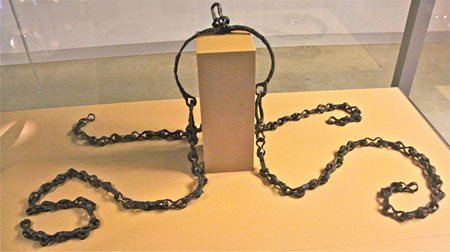

The use of metal products had become commonplace from the mid 2nd century BC. Ironically, the abundance of iron may have been one reason for the decline of oppida like Kelheim and Manching as increased inter-tribal warfare/raids, that were aimed at securing slaves for the lucrative Roman market, eventually weakened many of the hillforts before 50 BC (P.S.Wells, "Iron Age Temperate Europe: Some Current Issues," Journal of World Prehistory, Vol.4, no.4, 1990, p.466).

Slave chains found at Manching (2nd/1st centuries BC)

A collection of grave finds (1st century BC) from the Kelheim area including iron weapons, an iron shield boss, bronze jar and a ceramic bowl.

Glass ring beads were locally produced at Kelheim as evidenced by the Minnesota University excavation (1987) that unearthed a variety of glass items including a chunk of unworked blue glass.

Unlike many 2nd/1st centuries BC Celtic sites in temperate Europe where there are few cemeteries, Kelheim has discovered 19 Middle to Late La Tene burial sites east of the oppidum in Kelheim-Gmund. It is one of the largest funerary assemblages in southern Germany. The graves reveal a marked increase in consumption of material with hoards and votive offerings containing iron, bronze and precious metals.

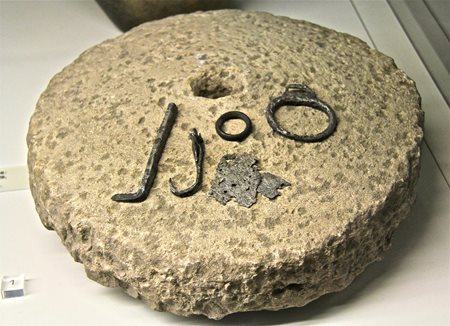

A millstone for grinding cereal crops and various iron finds from the Mitterfeld area within the Kelheim oppidum.

Evidence from plant remains have shown that cereal crops were processed within the oppidum revealing control of this resource in the region and faunal age patterns show that pigs were farmed inside the oppidum but cattle was probably brought in from surrounding communities ( M.L.Murray, "Socio-Political Complexity in Iron Age Temperate Europe: A Dialectical Landscape Approach," in D.A. Meyer et. ali., Debating Complexity - Proceedings of thec 26th Annual Chacmood Conference, University of Calgary, 1996, p.408).

Manching's archaeology began in Nazi Germany in 1936 when an airfield was built on the site. Its first finds were rescued by a local archaeologist who exhibited them in Ingolstadt Museum. World War II found the site heavily bombed by the Allies who returned in 1955 to redevelop the military airfield. A German archaeologist, Werner Kramer, was quick to seize an opportunity and, along with a generous grant from the U.S. Air Force, he began a 4 month rescue excavation that saw the digging of 7.5 kilometres of trial trenches. Furthermore, a large 6,680 sq. metres site was excavated in the middle of the oppidum.

The result of the 1955 excavation was revolutionary to the understanding of Late La Tene culture in temperate Europe. No longer was the ancient Roman writers' view correct that only barbarians lived in the Germania regions. Here was a sophisticated and highly productive urban settlement (P.S.Wells, The Barbarians Speak, (N.J. 2001), pp 28-30).

Apart from bronze, silver and gold coins minted at Manching, iron ingots were a currency used to trade with Roman merchants who were keen to exchange more exotic goods like wine, garum, jewellery and fine pottery from the empire for these iron ingots as well as leather goods, slaves and copious agricultural products.

There were 5 varieties of wheat grown locally as well as barley, oats and millet. Iron ploughs were able to exploit heavier soils whilst iron scythes made harvesting far more efficient. Agricultural productivity increased significantly during the Late La Tene period.

A collection of iron tools on display at Manching Museum. Over 200 different types of iron tools were found at Manching. The spotlighted tool on the right is for leather-working whilst the numerous axes found randomly at Manching probably implies that iron workers combined their skills with timber-cutting for the furnaces.

A collection of iron weapons and kitchen implements such as a sieve.

A simple fishhook masterly designed and manufactured.

During Manching's peak period of power c.100 BC, it is estimated that 3,000-5,000 people lived and worked within the oppidum's 380 hectares which was encircled by 7 kms of 'murus gallicus', Kelheim-style walls. This great wall required 60 tons of iron nails to secure the massive timbers (B. Cuncliffe, The Ancient Celts, London, 1997, p.225).

Manching's original 'murus gallicus' wall was later rebuilt in the Kelheim style. An impressive 4 metres high double- gateway greeted visitors to this centre of manufacturing and trade. Up to the year 2005, there have been 3 pottery kilns excavated which were designed to withstand temperatures over 800 degrees Celsius. Only a small proportion of the oppidum has been excavated. According to the German Archaeological Institute only 8% of its 380 hectares has been thoroughly researched.

An attractive display at Manching Museum of smooth, wheel-thrown, glazed pots. Over 800,000 sherds have been systematically registered and documented revealing 10 different types of ceramic wares. One Manching study of 175,142 sherds found that 35% were smooth wheel-turned pottery, 25% coarse domestic ware, 24% graphite-clay ware (graphite was imported for this high temperature resistent, oven ware), 11% fine painted ware and 5% non-graphitre clay, comb-decorated pottery (P.S. Wells, "Resources and Industry" Chapter 12 in M. Green's, The Celtic World, N.Y. 1995, p. 220).

An attractive display at Manching Museum of smooth, wheel-thrown, glazed pots. Over 800,000 sherds have been systematically registered and documented revealing 10 different types of ceramic wares. One Manching study of 175,142 sherds found that 35% were smooth wheel-turned pottery, 25% coarse domestic ware, 24% graphite-clay ware (graphite was imported for this high temperature resistent, oven ware), 11% fine painted ware and 5% non-graphitre clay, comb-decorated pottery (P.S. Wells, "Resources and Industry" Chapter 12 in M. Green's, The Celtic World, N.Y. 1995, p. 220).

Celtic religion has been described as 'fertile chaos' in that their religious beliefs changed over time as well as varied according to tribal locations. Added to the archaeological 'rich array' of Celtic finds is the biased, thus, confusing accounts of the ancient Roman writers (B. Cuncliffe, The Ancient Celts, London, 1997, p.183). With minimal indigenous written evidence, one falls largely back on archaeological evidence. In the case of Kelheim and Manching oppida, it is the iconography in Celtic art, burial finds, votive offerings and religious shrines and shafts. As Professor Barry Cuncliffe states, "From this huge mass of disparate evidence, sometimes distorted and usually partial, some semblance of the religious systems of the Celts can be reconstructed." (B. Cuncliffe, Ibid. p.183).

Animals played a special role in both the secular and religious life of the Celts. Ritual was not confined to the four walls of a temple or to regular ceremonies; rather, it was all-pervasive (M. Green, Animals in Celtic Life and Myth, N.Y., 1998, p.4). At both Kelheim and Manching there is strong evidence of a deer cult.

A bronze statuette of a deer found at Kelheim oppidum (150 BC-50 BC).

A large ceramic container with a centrally-positioned stag motif found at Manching oppidum. Interestingly, the leaping stag has a bridle in its mouth indicating domesticity. The large pot was excavated near the central sanctuary of Manching and is dated the 2nd century BC.

Animal husbandry was an important agricultural pursuit especially pigs. One study of animal bones found Manching showed 99% of the bones were domestic animals with pigs representing 1,350 of the studied animals, followed by sheep/goats at 800 animals, cattle 700, dogs 139 and horses 77. Strabo commented that the Celts had enormous supplies of sheep and pigs supplying not only Rome but most regions of Italy too (M. Green, Ibid., p.249).

Although this statue depicts a wild boar which was rarely part of Manching's diet, its association with the gods is still clear.

A fragment of an iron horse. Epona, the goddess of horses and agricultural fertility, was widely worshipped in temperate Europe.

The piece de resistance of archaeological finds at Manching is a model of a tree with ivy leaves and fruit made out of wood covered with sheets of bronze and gold. Single trees, woods and groves were sacred to Celtic cult worship. Perhaps the legacy lives on in the form of the maypole erected each year in the centre of many German towns.

The 'Tree of Life' allegory was found elsewhere in Germany with numerous Jupiter columns symbolising trees and at Pesch, in Germany, a temple was unearthed to the mother goddesses that had a great tree as its central cult focus.

Ladenberg's impressive Maypole.

A Roman military presence arrived at both Kelheim and Manching in AD 30, well after their demise, with the construction of small forts (20-80 auxiliaries) at Weltenburg and Oberstimm respectively. Around AD 80 new forts were built nearby at Kosching, Eining, Regensburg-Kumpfmuhl and Straubing which linked the region into a network of defences called the limes. An inscription found at Eining referred to Emperor Titus (AD 79-81).

Above are two hulls of Roman military ships that were found at Oberstimm in 1986 and, after 8 years of restoration work, were ready for display in 1994. These swift vessels (c. AD 100-110) were used for patrols and escort trips along the Danube River system.

A collection of finds from the Oberstimm fort which reveal the many activities of various trades within the fort. The scales in the background is a reconstruction (Manching Museum).