However, Caesar’s account is superficial or at worst ‘artificial’. It does not allow for regional variations with emphases on particular deities or changes over time. For example, changes resulting from a tribe’s proximity to the Mediterranean Graeco-Roman zones and new urban influences from the southern settlements in Gaul such as Narbonne and Marsailles. Traditional religious practices were in decline in the south of Gaul (Davies 2000:75).

Religion in Celtic Gaul is a complex problem because of the nature of the evidence: the ‘useful’ yet biased Roman written sources and the conspicuous absence of an indigenous written story. Some scholars have tried to understand Continental Celts by studying the literature of the ‘Insular Celts’ from Ireland and Wales. Unfortunately, the former was documented centuries later circa.11th-12th centuries A.D. These stories and sagas were also sanitised or filtered by Christian monks. Welsh accounts in verse and prose were written down even later. Once again useful but limited application to understanding the Celts in Gaul (Davies 2000:76-77).

Archaeology can restore the balance somewhat although it too has an ‘equally varied mix of data’ taken from:

- art imagery or iconography as depicted on artifacts

- the functions and contexts (locations found) of the artifacts themselves

- their belief systems as witnessed in their burial practices, votive offerings and sacred structural sites like shrines and shafts (Cuncliffe 1999:183-184).

In order to recognise the main aspects or ‘features constant’ of religion in Celtic Gaul it is useful to visit the Roman view of Celtic religion in Gaul; then, we can appreciate how religion in Gaul was ‘redefined’ under the Romans in another section on Roman Gaul.

Roman ‘interpretatio’:

1. Caesar’s observations- ‘Commentaries on the Gallic Wars’ (Book 6):

“The nation of all the Gauls is extremely devoted to superstitious rites” (BG 6.16).

|

|

|

FUNCTION

|

|

Mercury

|

Lugus

|

Inventor of all arts, assists travel and commerce

|

|

Apollo

|

Maponus

|

Averts disease

|

|

Minerva

|

Epona

|

Instructs in industry and crafts

|

|

Mars

|

Teutates

|

Controls warfare

|

|

Jupiter

|

Taranis

|

‘Supremacy among the gods’, sky god, symbols of the wheel and thunderbolt

|

An interesting comment from Caesar was that the Gauls descended from one god called 'Dis Pater', the equivalent Roman god of ancestors and the Underworld. Caesar states that it was a tradition instilled by the druids (Cunliffe 1999:187).

Caesar also relates how Gauls dedicated spoils to the gods. For example, before a battle goods are stacked in a pile in the hope that this offering will help them win. If the battle was successful animal offerings to the war god followed and no one on pain of death removed these rich goods from the sacred ground (Cuncliffe 1999:192).

2. Lucan’s view: The Roman poet Lucan (A.D.39-65) in Pharsalia simplifies even more than Caesar by naming only three Celtic deities: Teutates (Mars), Taranis (Jupiter) and Esus (Mercury). According to Lucan, who lived during Nero's principate, these three deities were to be pacified by human sacrifice: drowning, burning and hanging respectively (Cunliffe 1999: 185).

Taranis (Jupiter) from Le Chatelet, Gourzon, Haute-Marne (Wikimedia commons)

Taranis (Jupiter) from Le Chatelet, Gourzon, Haute-Marne (Wikimedia commons)

Esus (Mercury) on the pillar of the ‘nautae’ Musee de Cluny, Paris. Wikipedia Common Le pilier des Nautes-(Musée National du Moyen Age, Thermes de Cluny)

Esus (Mercury) on the pillar of the ‘nautae’ Musee de Cluny, Paris. Wikipedia Common Le pilier des Nautes-(Musée National du Moyen Age, Thermes de Cluny)

3.Human sacrifice:

Many Roman commentators remarked on this practice among the Celts of Gaul such as Diodorus Siculus (1st century B.C.):

“They stab [their victim]… and foretell the future from his fall…from the convulsions of his limbs and from the spurting blood”. However, Cunliffe reminds us that “convincing evidence of human sacrifice is surprisingly rare in the archaeological record " (Cuncliffe 1999:192).

A rare and fascinating example of what is generally considered human sacrifice for ritual purposes can be found at Acy-Romance, a village of the Remi tribe (180 B.C.) that was discovered in 1979 by aerial photography. Over 20 years of difficult excavation work was carried out largely by volunteer diggers and of course, a small team of archaeologists who had to maintain the goodwill of neighbouring French farmers. Three graves that each contained a seated and dried burial were situated in a line outside two 'temple' buildings (postholes were found) as well as another grave with an outstretched axe victim, provided strong evidence of human sacrifice.

See: www.gaulois.ardennes.culture.fr/en#/en/uc/02_03_02/t=Some%20highly%20unusual%20graves

Indigenous deities: Other deities that had no Roman equivalent were likely to keep their indigenous Gallic names:

Damona, goddess of fertility,healing and hot springs especially around Burgundy region

Sequana, water goddess of healing especially at Les Sources de la Seine in Burgundy.

Rosmerta, goddess of fertility and abundance

Arduinna, goddess of forests and wild animals

Cernunnos, god of virility, the ‘Horned One’

Arvernus (Mercurius Dumias), main tribal deity of Arverni, god of the mountain

Cobannus, a local Celtic war deity

Icovellauna, goddess of ‘Beautiful water’; Mediomatrici tribal deity

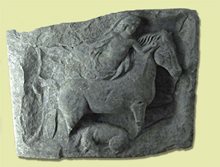

Epona: the horse goddess was one deity of the Gauls that was adopted by the Romans too. Many of Caesar’s recruits from Gaul went into the auxiliary cavalry cohorts.

Epona riding side-saddle from Champoulet (Loiret, Centre, France

Epona riding side-saddle from Champoulet (Loiret, Centre, France

Epona riding bareback from Allerey (Côte d'Or, Bourgogne, France)

Epona riding bareback from Allerey (Côte d'Or, Bourgogne, France)

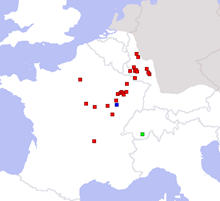

Distribution map based on Epona’s finds.

Distribution map based on Epona’s finds.

Notice the concentration of these finds in central Gaul along the rivers of the Rhone-Saone-Seine corridor mostly territory of the Aedui federation of tribes. A key element of the Aedui tribe’s economy was the horse. Apart from military purposes the horse was used for civilian transportation. Epona was worshipped by all Aeduan groups as a patroness of the arts and crafts (especially to do with warfare) and of course, as patroness of horsemen and horses (chariots and wagons were popular). In Rome itself Epona was often also linked with Minerva (Crumley 1987:139-140).

Under the Romans, worship of Epona was geographically widespread although finds are generally sparsely distributed. For example, Africa has only one Epona find.

Thanks to http://www.epona.net/distribution.html

Thanks to http://www.epona.net/distribution.html

Belisama: goddess of protection, light, summer, the forge and crafts ( Roman equivalent of Minerva)

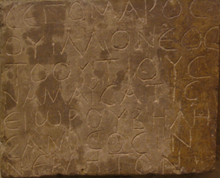

In this 7 line inscription written by Segomaros, he dedicated a sacred area or nemeton to Belisama ( found in Vaison La Romaine, Provence, Musée Calvet, Avignon)

In this 7 line inscription written by Segomaros, he dedicated a sacred area or nemeton to Belisama ( found in Vaison La Romaine, Provence, Musée Calvet, Avignon)

Damona: goddess linked to hot springs for healing. A stone statue as well as nine inscriptions with her name have been found in Bourbonne-les-Bains, a commune in the Haute-Marne department in north-eastern France ( see musees-de-france-champagne-ardenne.culture.fr/musee_france/b1.jpg) as well as four inscriptions from Bourbon-Lancy in the Saône-et-Loire department , region of Burgundy (see www.culture.gouv.fr/culture/dp/daf_archeo/pages/catalogue/dAf025/abstract_daf25.html)

Horns of aurochs mineralized by a long stay in thermal springs at Bourbonne-les-Bains

Horns of aurochs mineralized by a long stay in thermal springs at Bourbonne-les-Bains

Sequana: Goddess of the River Seine especially noted for her healing springs at Les Sources de la Seine in Burgundy.

One of the 150 oak votive offering statuettes found between 1963-1966 at Sequana's Sources de la Seine (Courtesy of Dijon Museum).

Dijon Museum's display of votive offerings found at Les Sources de la Seine near Chatillon-sur-Seine (Courtesy of Dijon Museum)

Rosmerta: goddess of plenty, ‘The Great Provider’.

Statue of Rosmerta (left) with cornucopia and Mercury (right) from Autun (Wikipedia Common)

Statue of Rosmerta (left) with cornucopia and Mercury (right) from Autun (Wikipedia Common)

Distribution of epigraphic inscriptions dedicated to Rosmerta (in red), and also to Cantismerta (green: one in Switzerland) and Atesmerta (blue: one in Champagne). Wikipedia commons QuartierLatin1968 (Owen Cook). According to this distribution map, Rosmerta was popular in north-eastern Gaul.

Distribution of epigraphic inscriptions dedicated to Rosmerta (in red), and also to Cantismerta (green: one in Switzerland) and Atesmerta (blue: one in Champagne). Wikipedia commons QuartierLatin1968 (Owen Cook). According to this distribution map, Rosmerta was popular in north-eastern Gaul.

In a forest near Koblenz on the German-French border a temple to Rosmerta and Mercury was excavated. Although evidence of a Gallo-Roman temple is clearly evident an earlier Celtic shrine existed there too.

The ‘temenos’ or sacred enclosed area is 19.2 long and 18.5 wide- Rosmerta/Mercury’s temple, Koblenz (http://koso.ucsd.edu/~martin/merkurtemple.htm)

The ‘temenos’ or sacred enclosed area is 19.2 long and 18.5 wide- Rosmerta/Mercury’s temple, Koblenz (http://koso.ucsd.edu/~martin/merkurtemple.htm)

Figurine recently found at Sous-Parsat, France thought to be Rosmerta.

Figurine recently found at Sous-Parsat, France thought to be Rosmerta.

Arduinna: In the Ardennes region of Gaul she is the patroness of the wild boars, a sacred animal of the Gauls. Linked to forested heights, to the moon and to wild animals her worship was popular in the Ardennes region named after her. The Ardennes or ‘deep forest’ is mostly in France but stretches out to the south of Belgium and also to Luxemburg and Germany. The worship of Arduinna in this region was so entrenched that in A.D. 565 the Christian church preached to the population of Villers-devant-Orval to forgo the worship of Arduinna. The Roman equivalent goddess was Diana.

Arduinna riding a wild boar

Arduinna riding a wild boar

The Sailors' Pillar of Notre Dame erected by the Nautae Parisiaci (Seamen of the City of Paris). Several Celtic gods are mentioned on the pillar's inscription. Here is Cernunnos with gold torcs around his antlers. For a good description of this important stone pillar of Tiberian origin see: www.chronarchy.com/esus/nautes-pillar.html

The Sailors' Pillar of Notre Dame erected by the Nautae Parisiaci (Seamen of the City of Paris). Several Celtic gods are mentioned on the pillar's inscription. Here is Cernunnos with gold torcs around his antlers. For a good description of this important stone pillar of Tiberian origin see: www.chronarchy.com/esus/nautes-pillar.html

Arvernus (Mercurius Dumias): the chief god of the Arverni, god of the mountain and worshipped in a sanctuary on Puy-de-Dome

View to Puy-de-Dome and Arvernus’ sanctuary on top.

View to Puy-de-Dome and Arvernus’ sanctuary on top.

Cobannus: Although this bronze statue of Cobannus (Mars) is Gallo-Roman in origin (A.D.125-175) it is likely that Cobannus was a local Celtic war deity from Gaul. (Getty villa, Malibu)

Cobannus: Although this bronze statue of Cobannus (Mars) is Gallo-Roman in origin (A.D.125-175) it is likely that Cobannus was a local Celtic war deity from Gaul. (Getty villa, Malibu)

Grannos: a god healing and hot springs. He was worshipped at Grand in the Vosges, Horbourg-Wihr in the Haut-Rhin and at Monthelon in Saône-et-Loire. In Limoges in Haute-Vienne a 10 night festival was held to this god in the 1st century A.D. Although linked to the Roman god Apollo, this festival does reveal the god’s popularity in this region of the Liovices tribe.

LIMOGES INSCRIPTION TO GRANNOS

POSTVMVS DV[M]

NORIGIS F(ilius) VERG(obretus) AQV

AM MARTIAM DECAM

NOCTIACIS GRANNI D(e) S(ua) P(ecunia) D(edit)

Translation: "The Vergobretus Postumus son of Dumnorix gave from his own money the Waters of Mars for the ten-night festival of Grannus". (Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Grannus)

Bormanus: another hot springs, healing god. Different regions had slight variations of the name: Borvo-ialum, La Bourboule (Puy-de-Dôme); Borvo-cetum, Burtscheid (près d'Aix-la-Chapelle); Bormenacum, Wormerich (près de Trèves); Borbona, Bourbonne-les-Bains (Haute-Saône); Borbone, Bourbon-L'Archambault (Allier); Burburinum and Bourberain (Côte-d'Or)

Braciaca : god of beer and malt with 5 places in Gaul linked directly to this god’s name.

This list is far from a complete list of Gallic deities. A least 270 deities are mentioned in inscriptions in Europe (MacCulloch 1911:23) and Cuncliffe (1999) agrees with the figure of 200 but warns the number was probably smaller as some gods/goddesses may have had their names repeated under different names (Cuncliffe 1999:184).

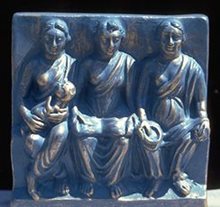

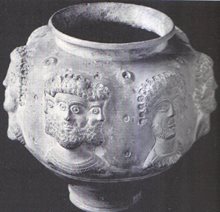

Triplism: Triplism or ‘the power of three’ is prevalent in Celtic religion. A pot in Bavay, northern France has a tricephalic or three-headed deity on it. The three Matronae or ‘Mother goddesses’ and the Saluviae trinity of the ‘springs’ existed in the Gallo-Roman period so it’s highly likely that the concept existed pre-conquest among the Celts of Gaul.

The Celtic trinity or nurturing ‘matronae’ (Vertault A.D. 100)

The Celtic trinity or nurturing ‘matronae’ (Vertault A.D. 100)

Glanum in Provence, altar to Glan and the three Glanicae (healing-springs deities)

Glanum in Provence, altar to Glan and the three Glanicae (healing-springs deities)

Reims

Reims

Bavay

Bavay

Condat

Condat

Here are three depictions of Cernunnos in a tricephalous form. Looking in several directions seems to infer the god’s ‘multiplicity’ of powers (Sopeña 2005). Davis (2000) believes that female deities may have originally been more important than male gods. Goddesses were portrayed more often in triplicate too emphasizing he believes their ‘potency’ (Davies 2000:83).

The Druids: Religion in Celtic Gaul was largely the reserve of the druids. Druidic teaching was based on memory and mostly oral history. Accordingly, Drinkwater (1983) states how the religion of Celtic Gaul became a ‘grey area’ after the Julio-Claudian princeps eliminated the druidic teachings that threatened a possible alternative culture with a ‘pan-Gallic’ (across all of Gaul) threat (Drinkwater 1983:11 206). Sadly, most religious knowledge went with them.

Celtic theology: One theory is that the Celts’ theology or religious thinking was based on simple binary oppositions similar to the Chinese yin/yang idea: male/tribe/sky/war versus female/place/earth/fertility. Balance, harmony and productivity will rule over chaos by following a regular annual cycle governed by the seasons of the year (Cuncliffe 1999:188).

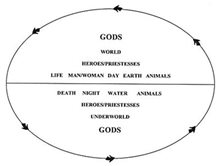

An interesting study of the Celts of Portugal by Teresa Júdice Gamito (2005) of the University of Algarve, suggests a similar ‘oppositions’ theory in the diagram below but with 3 main oppositions: Life/Death, Day/Night, Earth/Water.

The cyclical and ever-changing nature of the universe is emphasized above. The circle was a popular Celtic motive in their art.

The cyclical and ever-changing nature of the universe is emphasized above. The circle was a popular Celtic motive in their art.

A constant cyclical movement animated their universe. Gods, animals and some humans - the heroes and the priestesses - penetrated both sides of this world and the Underworld. The supreme god was, at the same time, the lord of both worlds. Animals, especially those most frequently worshipped, such as the wild boar, the stag, the serpent, the bull, the cat, the dog and some birds - the duck and the swan - could come and go between this world and the Underworld. This was certainly true of the heroes and priestesses who could easily step into and from both worlds (Gamito 2005). See: www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_11/gamito_6_11.html

A constant cyclical movement animated their universe. Gods, animals and some humans - the heroes and the priestesses - penetrated both sides of this world and the Underworld. The supreme god was, at the same time, the lord of both worlds. Animals, especially those most frequently worshipped, such as the wild boar, the stag, the serpent, the bull, the cat, the dog and some birds - the duck and the swan - could come and go between this world and the Underworld. This was certainly true of the heroes and priestesses who could easily step into and from both worlds (Gamito 2005). See: www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_11/gamito_6_11.html