I. Who were the Celts?

The hub of the wheel:map of France with the tribes of Gaul

Wikimedia.org

Wikimedia.org

http://www.celtnet.org.uk/gaulish-tribes.html

A better, more colorful and detailed tribal map.

The revolving hub of Celtic tribal life is the land. The land’s topography and climate would dictate the tribe’s level of agriculture, stock breeding, timber supplies, industrial activity (ceramics, mining and metallurgy) as well as the extent of isolation or ‘contact culture’ with other tribes or civilisations (Woolf, 2003).This ‘contact culture’ prior to Roman conquest mainly refers to the tribal land’s proximity to the Mediterranean Sea, the Greco-Roman maritime trading mecca. Proximity to Mare nostrum (‘our sea’) the Roman name for the Mediterranean Sea, greatly affected the amount of Greco-Roman influence on Celtic tribal societies.

As a rule of thumb, tribes in the north of Gaul were least affected by a Mediterranean or Greco-Roman culture. However, central tribes like the Aedui who controlled the Rhone/Saone Rivers network and especially southern tribes like the Volcae nearer the coast were affected earlier and more significantly. Not all tribes saw the ‘Mediterranean effect’ as positive and culturally enriching. For example, the west-central Arverni tribe showed a resistance to it where as their neighbouring tribe and arch-enemy, the Aedui, generally encouraged Mediterranean culture contact.

The land of the Celtic tribes of Gaul was diverse just like their individual cultures. One way of looking at the diversity of Gallic tribal lands is to view Celtic Gaul as a series of rock pools that are affected by crashing waves from various directions resulting in ‘local micro-environments’ (G.Woolf, 1997). When you look into rock pools one always finds similarities among them but also many differences.

Some of Gaul’s geographical diversity includes:

- The mountainous land in the east along the Swiss Alps of today as well as the mighty Rhine River that created a natural border and a slight buffer against other tribal invasions from Germany

- Windswept Atlantic coasts of the western tribes

- In the north, temperate, low marshy and thickly-forested lands of the Nervii created an awesome obstacle

- In the warmer, drier southern regions of Gaul tribes found themselves well suited to growing new Greco-Roman crops like grapes and olives from an earlier time and consuming more and more new goods

- West-Central Gaul ranged from the more isolated mountainous ‘Massif Central’ (1/6 total area of France) of the Arverni tribe to the rich open farm lands along the upper Rhone/Saone/Loire/Seine river valleys. This central region experienced a warming, Mediterranean climate called the Roman Climatic Optimum from 300 B.C. to A.D. 200. This climatic phenomenon allowed the expansion of warmer crops and fruits like grapes, olives and wheat (Crumley, “Alternative Forms of Social Order”2003:141)

This diversity of topography in France today can be seen in its “deep gorges, rugged pinnacles, windswept plains and coastlines, and gently rolling hills and valleys- frequently within sight of one another” (Crumley 1987: 404).

Finally, Gaul’s central strategic position in western Europe ensured prosperity for tribes or groups who could control key geographical features like rivers, mountain passes and ports (Crumley 1987:405).

Who were the Celts?

Unfortunately, this is no easy question to answer. Intense academic debate surrounds this question. Scholars have tried to define the Celts using several methods: analyzing linguistic patterns, comparing common cultural heritage as evidenced in archaeology, ancient written sources and even DNA surveys.

1. Tracing linguistic patterns in order to verify a common ancestry:

According to Professor Barry Cuncliffe's , The Ancient Celts (1999) there are basically two Celtic languages:

- ‘Continental Celtic’ that placed Gaul in the central Celtic linguistic zone and,

- ‘Insular Celtic’ of the Irish, British and far western Gaul of Brittany. ‘Insular Celtic’ is further subdivided into Brythonic ( or 'P-Celtic' spoken by Welsh, Cornish and Bretons) and Goidelic ( or 'Q-Celtic' spoken in Isle of Man, western Scotland and Ireland)

Further reading: (Cunliffe 1999:21-27)

Link to Brythonic/Goidelic information:http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/general/ie-lg/Celtic.html

Linguistic evidence has been found in place names such as Lugdunum and Glanum both named after Gallic deities, inscriptions (stone, pottery and bronze), coins (minimal) and mythology.

1st century B.C. coin of Pictones tribe

Coin link: http://www.kernunnos.com/dlt/map.html

A famous example of Gallic writing is the bronze Colignay calendar. Its 73 pieces reconstruction in Lyon’s Gallo-Roman Museum measures 1.48 m wide and 0.9 m high. One theory believes:

- the bronze tablet was made circa. mid 1st to early 2nd century A.D.

- it documents 354 days in a year

- the 12 months have 29/30 days

- the word ‘atenoux’ often repeated may represent the Gallic word for ‘full moon’ (Athena Review image archive at http://www.athenapub.com/lyoncal1.htm)

- the druids or Gallic priests devised it based on both the solar and lunar calendars

- a month was divided into two fortnights: a ‘light half’ and a ‘dark half’

- leap years were taken into account

For further information http://www.roman-britain.org/coligny.htm

The ‘Colignay Calendar’, Gallo-Roman Musee, Lyon.

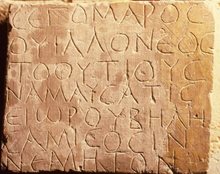

Another Graeco-Gaulish inscription that was discovered in Vaison La Romaine is the stone slab record of a gift of land to the goddess Belesma by Segomaros, son of Villonos, citizen of Nemauso (Nimes).

Musee Calvet, Avignon

Musee Calvet, Avignon

2. Using archaeological evidence of cultural significance to reveal common heritage:

Here historians have defined the evolution of Celtic culture into distinct cultural eras based on the discovery and dating of some famous archaeological sites where Celtic cultures were first discovered

It should be noted that there is no suggestion that the cultures below originated at these sites only that the cultures are ‘typical’ of these famous sites. This cultural definition of the Celts is thought to be the most acceptable and worthy way to define the Celts. “The heart of the Celtic world” was the Halstatt and La Tene cultures (Vitalli 2006:2).

The Halstatt culture:

Origins: At Halstatt in Austria George Ramsauer excavated from 1846 for 18 years finding over 1000 graves. Along with a salt mine, this series of excavations revealed among other things amber jewellery from the Baltic Sea, glass from Italy, textiles, axes, ivory from Africa, leather goods, a rucksack, a tassled cap, a horn cup and ceramic vessels. These people who lived off the salt trade were called ‘Celts’.

Dating: Dating methods established its beginnings circa.750 B.C. and its end around 450 B.C. In the case of Halstatt itself its decline occurred as salt mines opened in other areas of central Europe.

A further dating breakup of the Halstatt culture period is:

Halstatt C – 750-600 B.C.

Halstatt D1 – 600 to 530 B.C.

Halstatt D2-D3 from 530 to 450 B.C. (D.E. Witt 2008;13)

Cultural finds: This incredibly rich archaeological find was labelled the “Halstatt culture” beginning a definition of Celtic culture along cultural/artistic lines. Sites that exhibited similar artifacts, artistic styles, mainly cremation burials in large mound tombs (tumuli) and metallurgy craftsmanship were labelled under the ‘Halstatt period”. An Iron Age culture had begun in Western Europe that took in central France extending eastward to Bohemia and Hungary. Crumley calls this era “the first Industrial Age” (Crumley 1987:241).

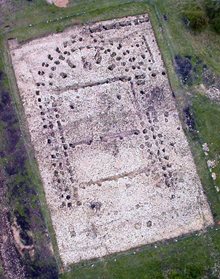

Halstatt C is characterized by bronze and iron weapons along with chariot equipment in ‘princely burials’. Aristocratic warrior elites are presumed to be in charge with the first appearance of hillforts called oppida. Animal husbandry and metallurgy activities suited these upland sites especially with a cool climate that existed in central Europe until 500 B.C.However, environmentally, land around these hillforts began to suffer as timber was cleared for industries. Mont Lassois, Burgundy is an example in France of one of these Halstatt oppida. Mont Lassois is a 7 hectare site. Recent excavations have unearthed a 35 metres long by 21.5 metres wide and 12-15 metres high building. One theory is that the ‘Princess of Vix” had her palace here around 500 B.C. The origin of this semi-urban site could be much older.

Aerial views of Mont Lassois oppidum

Halstatt leadership: Politically, one theory states that the regular spacing of territories indicated ‘autonomous complex chiefdoms’ or independent clan-based governments (Witt 2008:15). However, another view believes that a more hierarchial regime existed along early ‘state’ lines (Kristiansen 1998:11). The grand Mont Lassois oppidum site with its impressive megaron-style ‘Royal House’ along with its closely neigbouring ‘princely tombs’ may support the latter contention of a wealthy, more centralised leadership.

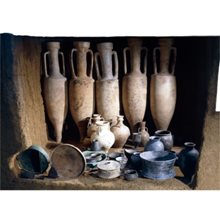

Drinking and feasting: The importation of Italian wine began during the Halstatt period. Although no great quantities of amphorae from this period have been found in oppida, Bettina Arnold argues that wine may have been transported in skins (now perished) as well as amphorae. The Halstatt elite began a tradition of feasting and drinking mainly for religious reasons and prestigious, social aggrandizement. Interestingly, the Hochdorf chieftain was buried with an impressive 5.5 litres drinking horn (Arnold 1999:86).

This tradition of generosity was to continue in Celtic society (Arnold 1999:72-73).

Decline of the Halstatt culture: By 6th century B.C. many of the Halstatt oppida were destroyed by fire. A consolidation of lowland settlements came into existence. Local indigenous problems are believed to be the main cause of this disruption along with a new trading impetus from the south of Gaul- the new Greek colony of Massalia. Expansion of the Mediterranean trade hastened this change by shifting ‘exotic’ trade away from central Europe to Spain (Witt 2008: 17).

Other excellent ‘Halstatt’ culture excavations are:

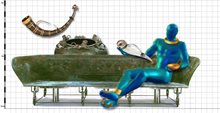

1. Hochdorf burial site near Stuttgart in Germany (550 B.C.):

Tomb tumulus

Layout of tomb

Bronze couch with chieftain: 45 years of age and 1.87 metres tall.

Bronze Cauldron :Height: 80 cm (without lions), diameter: circa. 104 cm. Capacity: 50

Original images courtesy of Constanze Witt and Württembergisches Landesmuseum; some digitally altered and reassembled after photographs published by Krauße 1996; also Biel 1985, 92 f., 149 f.

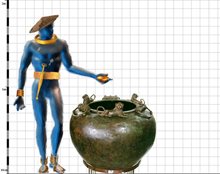

2. The famous Gallic ‘princess’ burial at Vix near Mont Lassois (Cote d’Or, Burgundy region):

Was the female occupant of unusual stature and gait a ‘princess’ or a ‘priestess’? Judging by the wealth of her burial goods like her jewellery she was held in very high esteem. She was part of her tribe’s elite.

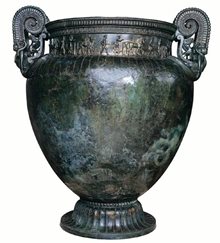

Note the size of the krater in relation to the ‘princess’ and waggon Châtillon-sur-Seine: Musée Archéologique

The Vix krater (bronze):1.64 metres high, 60 kgs and capacity 1,100 litres of wine.Musee du pays Chatillonnais Link: http://www.musee-vix.fr/fr/index.php?page=38

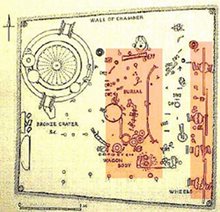

Plan of Vix

Plan of Vix

R. Joffroy and M. Moisson

R. Joffroy and M. Moisson

Halstatt culture was influenced by the Etruscans from northern Italy but Halstaat craftsmen still showed much unique creativity and craftsmanship especially in the new use of iron. Its influence extended largely over central Europe including central Gaul around Burgundy, the land of the Aedui tribe.

At Bragny-sur-Saone in Burgundy numerous Etruscan items have been recovered along with Golasecca (northern Italian) culture pottery. Also, pottery found there from Massalia (southern Gaul on the Mediterranean coast) reveals the fact that the Rhone River corridor was in operation too. Northern Italian prestige goods were mostly imported into Halstatt Gaul from two corridors - the passes of the far northern Alps and the Rhone River via Massalia (established by the Phocian Greeks in 600 B.C.).

Burgundy, France was a region controlled by the Aedui tribe in the above map.

(link Wikipedia common: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hallstatt_LaTene.png)

Halstatt link 1: http://www.kelten.co.at/index_en.php?sub=fi_hallstatt_en#content

Textiles link 2: http://dressid.nhm-wien.ac.at/textile_e.html

Leather goods link 3: http://www.kelten.co.at/index_en.php?sub=fi_textil_en#content

Salt mines link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B4ba3oycEX0&feature=related

Large burial mounds link 4: http://www.unc.edu/celtic/catalogue/grave/Hochdorf.html

First Industrial age link: http://anthropology.unc.edu/french/rd/rd_ch6.html

Hochdorf link 5: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/hochdorf1.php

Vix burial site link 6: http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/Barbarians/Sites/Vix/Vix_site.html

Vix jewellery link 7: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/vix1.php

Central Europe map link 8: http://bcs.fltr.ucl.ac.be/fe/11/GAUL/IMAG/01Carte1.jpg

The Golasecca culture:

Recent studies of the Golaseccans from northern Italy have verified the important role that these people had during the 8th- 6th centuries B.C. in extending trade into the Alps and beyond into Gaul. In search of tin and amber these merchants traded prestige goods with the Halstatt elites in central Europe including Gaul. They were able to develop a form of writing too and extended their influence by arranged marriages between the Etruscans and Celtic elites.

Courtesy: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Hallstatt_culture.png

La Tène culture:

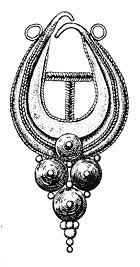

In 1857 in a lake at Neuchatal, Switzerland, Hansli Kopp found 40 weapons scattered in the mud during a very dry season. A series of wooden poles were also observed. Interpretations of the site have varied from a Swiss village built on piles to an armoury, a memorial site to a great battle and the most recent interpretation, an offering sanctuary to a Celtic cult. Years of excavating have revealed 800 weapons, 400 fibulae (brooches), shields, iron ingots, parts of vehicles and many votive offering objects totalling over 3000 artifacts.

This site was called La Tène. Other sites throughout Europe that displayed similar material culture and style were also known as La Tène cultural sites. La Tène culture spread rapidly across Europe from the 5th century (circa. 450 B.C.) declining in the early 1st century A.D.

It’s believed that the La Tène tribes migrated from eastern Europe bringing their horsemanship and iron-making knowledge with them. In the Marne Department in France a large migration into the La Tène area is witnessed by the discovery of over 191 Gallic cemeteries.For example, in the cemetery of Les Croncs, at Bergères-les-Vertus, over a thousand graves have been opened (Hubert 1934:4) see: http://www.electricscotland.com/HISTORY/celts/Celt1A.pdf

However, another point of view about the migration of the Celts believes that at the British indigenous people may owe their heritage to ‘Celtic’ migrations that occurred well before the La Tène period beginning with Neolithic migrations from Anatolia.Latest DNA testing has linked a significant number of British in the western half of Britain to the Iberian peninsula peoples (Spain). There was surprisingly little DNA correlation to central European ‘Celtic’ people’; therefore, adding weight to an earlier Neolithic Celtic migration to Britain via Spain.

Judging from grave artifacts, La Tène culture was a more militaristic culture than Halstatt such as two-wheeled chariots rather than four-wheeled carts and fighting weapons rather than ceremonial ones. It tended to return politically to decentralisation of tribal territory and capitals and they were not generally united under a single leadership. A warrior aristocracy along with wealthy farmers with weapons replaced the smaller Halstatt elite cultural groups especially around the Marne River valley areas in France to Bohemia in the east (Witt 2008: 18). Oppida returned with fortified earthen walls although they were now safely situated more inside the territory enabling lowland farmlands to continue around them (Crumley 1987:405). Consequently, a pattern for Europe’s future was set with mixed agriculture and husbandry: horses, sheep, pigs, goats and cattle.

Arranged marriages among the different tribes along with hostage practices and ‘frequent negotiations’ (Crumley 1987: 406) made for a complicated kinship and alliance-based political system that ebbed and flowed with political/economic fortunes.

Economically, mining and possibly slaves from the Seine River areas in the west of Gaul were traded along with the iron-working skills of the Moselle River areas (Germany) to the east.

Further research has led to the division of the La Tène period into four main periods first based on fibulae/brooch styles (Otto Tischler 1885); then, based on funerary goods by Paul Reinecke 1909:

La Tène A (very Early 475-400 B.C.)

La Tène B (400-250 B.C.)

La Tène C (250-100 B.C.)

La Tène D (100-20 B.C.)

The La Tène art style has been found throughout Europe including Britain, Ireland, the Iberian peninsula (Spain/Portugal), Romania and of course, Gaul (France).

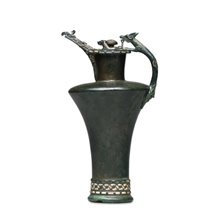

Basse-Yutz flagons, Lorraine, France, Iron Age, about 450 B.C. courtesy British Museum.

These flagons from Basse-Yutz, in Gaul reveal an Etruscan influence from northern Italy. The flagons were used for pouring wine, beer or mead at feasts. The British Museum purchased these flagons and other grave items from Leo Morel at Somsois near Vitry-le-Francois, France in 1901, a controversial sale at the time.

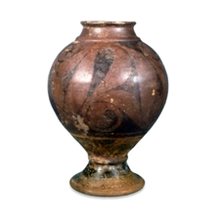

The Prunay vase 400-350 B.C. (Leo Morel collection- British Museum)

La Tène artifacts are often grave goods that feature warfare, personal ornaments and possessions. Other foreign influences were Greek and Thracian resulting in a unique stylistic, ‘abstract’ art evolved using spirals, trumpet shapes and ‘vegetal’ patterns. Later human heads were mixed in too!

An example of an Early La Tène grave was found in the Bliesbruck-Reinheim European Archaeological Park on the eastern border of France and Germany. The tumulus or mound tomb of the ‘Princess of Reinheim’ was found in 1954. Inside was found a magnificient gold bangle, a pipe- shaped bronze jug, a gold torc and a bracelet.

http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/images/reinheim/plan.php

http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/images/reinheim/plan.php

To see a plan of the grave with the items found within it click on this link:

http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/reinheim.php

What materials were used by La Tène craftsmen in this grave?

DNA testing link See: Steven Oppenheimer’s, Myths of British Ancestry (2006).

Link: http://class.csueastbay.edu/anthropologymuseum/2006IA/DNA_PDFS/mt&yDNA/Oppenheimer2006.pdf

Neuchatel link:

http://www.myswitzerland.com/map/?x=561256&y=204711&lang=en&type

swords link: http://www.beloit.edu/logan/exhibitions/virtual_exhibitions/before_history/europe/station_la_tene.php

Basse-Yutz link 1:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pe_prb/b/basse-yutz_flagons.aspx

Basse-Yutz link 2

http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/Barbarians/Maps/B-YMap1.jpg

Other grave goods link 2:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pe_prb/t/the_prunay_vase.aspx

Prunay vase link:

http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/pe_prb/t/the_prunay_vase.aspx

Personal ornaments link: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/reinheim.php

Stylistic art link: http://www.unc.edu/celtic/images/216295.html

‘Vegetal’ art link: http://www.unc.edu/celtic/images/216452.html

Gold bangle link: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/reinheim4.php

Pipe-shaped bronze jug link: http://www.laits.utexas.edu/ironagecelts/reinheim.php

Below you can admire the La Tène style decorations from jewellery found in Spain. For a detailed study of Celtic art in Spain see: http://www4.uwm.edu/celtic/ekeltoi/volumes/vol6/6_3/gonzalez_ruibal_6_3.html

Figure 43. Earring from northern Galicia. After Pérez Outeiriño (1982).

Figure 44. Earring from Afife. After Pérez Outeiriño (1982).

Figure 44. Earring from Afife. After Pérez Outeiriño (1982).

Figure 45. Earring from San Martinho de Antas. After Pérez Outeiriño (1982).

Figure 45. Earring from San Martinho de Antas. After Pérez Outeiriño (1982).

Here’s a British La Tène burial Iron Age from Welwyn, Hertfordshire, England (circa.50-20 BC)

A bucket, spoon and pan found in a late La Tène grave by Sir Arthur Evans in Aylesford Cemetery, outside Maidstone, Kent, England in 1886. It was similar to funerary items found in northern Gaul.

A bucket, spoon and pan found in a late La Tène grave by Sir Arthur Evans in Aylesford Cemetery, outside Maidstone, Kent, England in 1886. It was similar to funerary items found in northern Gaul.

3. Using ancient sources to define the Celts:

Scholars have used ancient written sources mainly from Greek and especially Roman writers to understand Celtic societies. However, ancient sources have combined to create a stereotypical image of the Celts of Gaul and this image was passed on to 19th - early 20th centuries’ scholars.

Below are some of those ancient sources, definitions and reliability/bias issues:

1.Herodotus , the first Greek travel writer and historian, is the oldest record of the name ‘Keltoi’ circa. 440 B.C.

2. The name of ‘Gaul’ was a Latin (Roman) word from ‘Galli’ or ‘Gallus’ meaning fowl. One theory is that Gallic warriors carried these fowl in cages with them. Interestingly, the fighting fowl is still a symbol of some French sporting teams.

3. Julius Caesar said,"We call them Gauls, though in their own language they are called 'Celts" (B. Cuncliffe, 1999:3).

Julius Caesar is an important source of information about Celtic Gaul. His military intervention into Gaul in 58 B.C. allegedly to assist the Celtic Aedui tribe from a massive Helvettii migration began Gaul’s subjugation (J.F. Drinkwater, 1983:5-6). Caesar recorded his exploits of this long improvised seven year series of Gallic campaigns in Commentarii de Bello Gallico. In seven books Caesar gives the reader many intended and unintended insights into the Celtic Gauls. To his ancient readers Caesar’s intentions were mixed.

Firstly, Caesar’s main intention was it to serve as propaganda back home in Rome. It was designed to boost his reputation- ‘dignatus’ and ‘gloria’ not in an arrogant ‘imperator’ (all-conquering General) way but as a servant of the Senatus Populus Quo Romanus (Roman Republic). After all, Rome’s bitter memories of the Gauls’ sack of its city in 390 B.C. ran very ‘deep and long’. (G. Woolf, 2003:61)

Secondly, he was desperate to quell opposition among his many Senatorial enemies in Rome as a consequence of his infamous, if not illegal, consulship in 59 B.C.

Thirdly, Caesar went from being on the verge of bankruptcy prior to the Gallic Wars to ‘extreme wealth’; in fact, he brought back so much gold from Gaul that its value declined by one third compared to the price of silver (G. Woolf, 2003:42). Rarely does his Commentaries mention plunder.

Therefore, his literary work has reliability and bias issues for the modern reader trying to gain a true depiction of the Celtic Gauls.

Caesar’s conquest of Celtic Gaul began a civilising mission for Rome, a type of ancient ‘manifest destiny’ called 'imperium Romanum'. He portrayed them as brave and fearsome (‘feroces’) although at times foolish warriors who constantly quarreled among themselves. In short, Gauls were primitive barbarians.

4. This primitive barbarian image was retained by the ancient writers who followed him. Strabo's Geography reveals the Romans’ implicit attitudes towards Celtic Gauls when he used put-down words like "Gallia Braccata" (trousered Gaul) and "Gallia Comata" (long-haired Gaul). By the mid-2nd.century Strabo described the Volcae Arecomici tribe as “no longer barbarians, since most of them have converted to Roman standards of language and lifestyle, and some have civic life too" (Strabo Geography 4.1.12 quoted in G.Woolf,2003:52-53).

5. Another Roman writer of Pompeii fame was Pliny the Elder. His Natural History was a lengthy attempt to analyse and rank the diverse products and lands of the empire. He stated that Rome was “the parent of all lands” with a duty to “unite the discordant wild tongues” (Pliny, Natural History: 3.39 in Ibid:53).

6. Even the Augustan poet Virgil in Aeneid has Jupiter uttering, " remember Roman, these are your skills: to rule over peoples, to impose morality (morem), to spare your subjects and to conquer the proud". (Virgil, Aeneid:6.851-3 in Ibid:57)

7. Other ancient writers who contributed to the 'primitive barbarian’ image were:

Polybius (204-122 BC), Poseidonius (135-50 BC), Diodorus Siculus (60-30 BC), Livy (59 BC-AD17), Tacitus( 55 B.C.-A.D.117), Pausanias (late 2nd cent AD) and Athenaeus (circa. AD 200). Generally, classical writers glorified the Roman achievement with Celts being 'worthy opponents' but 'primitive barbarians' (B.Cunliffe.1999:7)

Classical writers’ link: http://www.utexas.edu/courses/ironagecelts/sources.html

8. By the end of the 1st century A.D. the Celts of Gaul had become acceptable to most Romans: 'bonus' (good) for the empire rather than 'matus' (bad). (B. Cuncliffe, 1999:10)

4. Using DNA to trace biologically Celtic heritage:

Professor Bryan Sykes in the Oxford Genetic Atlas has attempted to compile a genetic map of Britain’s DNA and to see if there is a Celtic biological tradition in Britain. Taking DNA samples from people’s cheek swabs, Professor Skyes concluded that the west half of Britain did reveal a common biological pattern that was not shared by most continental European groups. The eastern half of Britain did share a larger proportion of continental biological tradition.

He proposed that most western half British shared a biological tradition more with the Iberian peninsula (Spain) and the coast of Brittany in France probably due to earlier Neolithic migrations and the prosperous Atlantic trade contact.

CONCLUSION:

The net effect of this debate has created ‘a fuzzy concept’ (B. Cunliffe, “The Celts” 1990 TV series) in answering this question, ‘Who were the Celts?”

The truth of “Who were the Celts?” probably lies in a combination of all four approaches. The Celts of Europe do have linguistic patterns that unite some Celtic tribes of Europe, there are many material cultural aspects like art styles, architecture and religion that present a common heritage, there are tit-bits of truth here and there in the ancient sources and the new DNA techniques present fascinating future possibilities for historians and archaeologists.

For the sake of brevity and emphasis on the archaeological record, this website’s study of the Celts of Gaul prior to Roman conquest will largely concentrate on the material cultural or archaeological aspects of the Celtic tribes. Both common and unique features of the Gallic tribes will be highlighted; thus, creating an interesting 'rock pool' experience.

| Back to Top |

Share